Like many young girls around the world, Sadaf Siddique and Gauri Manglik devoured stories of white girls and characters from Britain and America.

In Canada, I, too, grew up with these heroines. But while I easily related to the precocious Ramona Quimby or the bookish Elizabeth Wakefield — characters who looked and presumably sounded just like me —Gauri and Sadaf didn’t see their own faces reflected on these pages.

For Gauri, who was born in India, and Sadaf, who is from an Indian community within Nigeria, the stories were an escape and a glimpse into a world other than their own. And, at the time, they didn’t see the problem. After all, their Indian culture was already part of their everyday experiences, they say.

But, when their culturewasrepresented, it was stereotypical or blatantly inaccurate. Sadaf remembers a scene inIndiana Jones and the Temple of Doomwhere characters were eating monkey brains. “Do you know that most Indians are vegetarian?” she asks. “Nobody eats monkeys.”

Years later, after moving to the U.S., the two women saw children’s books through fresh eyes. Their own children were being raised in America, taught in American schools, immersed in American culture. Books were supposed to provide an opportunity to keep their culture alive in the next generation, but these moms struggled to find titles that told their own stories.

Only11 percent of children’s bookspublished between 1994 and 2016 contained people of color or First Nations content and characters. “Why do all books say 'mom' and 'dad' and not 'ama' or 'mama' or 'papa'? Why are all the books about bagels and pizza?” Gauri wondered.

Sure, Gauri and Sadaf did find many books that helped them share accurate representations of South Asian cultures with their children, but they had to dig, and many titles weren’t making it to the U.S. “There’s no market for multicultural books,” local publishers would tell them.

Gauri and Sadaf wanted toprove the industry wrong. In 2016, they devised a plan. The women would seek out South Asian voices and themes in children’s books and curate the best picks in one place. “Amazon is a jungle,” says Gauri. “Until you know something exists, it’s not always that easy to find it.” They launchedKitaabWorld, an online bookshop, and later became ambassadors for book diversity, working with communities to bring South Asian stories to libraries and classrooms and amplify the voices of diverse writers.

The biggest gap, they say, is “casual diversity” — Indian names in place of Sam or David, for example.

With theirCounter Islamophobia Through Storiescampaign, the women curated book lists likeMuslim Kids as HeroesandFolktales From Islamic Traditionsto offset the rise of hate speech and the “vilification of entire communities with one single broad stroke” by the current American political leadership. That campaign inspired their first book,Muslims in Story, published in 2018.

They’re challenging institutions and educators to expand their own understanding of diversity too. “People think they can check the diversity box, like if they have one book on India, they think they’ve covered it,” Sadaf says. “What we wanted to showcase is the multitude of stories. Just like any other community, there’s a lot of nuance.”

The biggest gap, they say, is “casual diversity”— Indian names in place of Sam or David, for example. “There’s a need for that underlying diversity that’s just built into the book rather than called out,” says Gauri. As their catalog evolves, other themes are beginning to emerge. KitaabWorld currently calls out stories about “girl power” and has many titles that feature characters with disabilities. They’ve had parents asking for books with two moms or two dads built into a story as well. “South Asian books are a little bit behind,” says Gauri.

I felt this feeling of mourning, imagining how different my life might have been had I found this book when I was 16.

Vivek Shraya

KitaabWorld does, however, stock two titles from authorVivek Shrayathat explore LGBTQ and gender themes with South Asian characters. Much like Gauri and Sadaf’s own motivations for starting KitaabWorld, Vivek approached the projects in response to her own experiences.

Vivek was only introduced to her first LGBTQ book,Stone Butch Blues, in her 20s.“I felt this feeling of mourning, imagining how different my life might have been had I found this book when I was 16,” she says. “I didn’t even know that LGBTQ books existed!” She wondered, though: what if the characters’ experiences mimicked her own, growing up with immigrant Hindu parents?

Vivek circumvented traditional publishers for her bookGod Loves Hairand other projects, and she believes that self-publishing is helping to elevate diverse voices. “Getting published in any genre is a huge challenge, especially for writers of color,” she says. This way she cansell books online直接向读者,而不是放弃创作control to publishers.

Traditional publishers are beginning to change their tune, and the argument that diverse books don’t sell just doesn’t fly anymore. “Look, we have books and we’re selling them,” says Gauri. “If you spotlight them enough and you provide the right context, they will sell.”

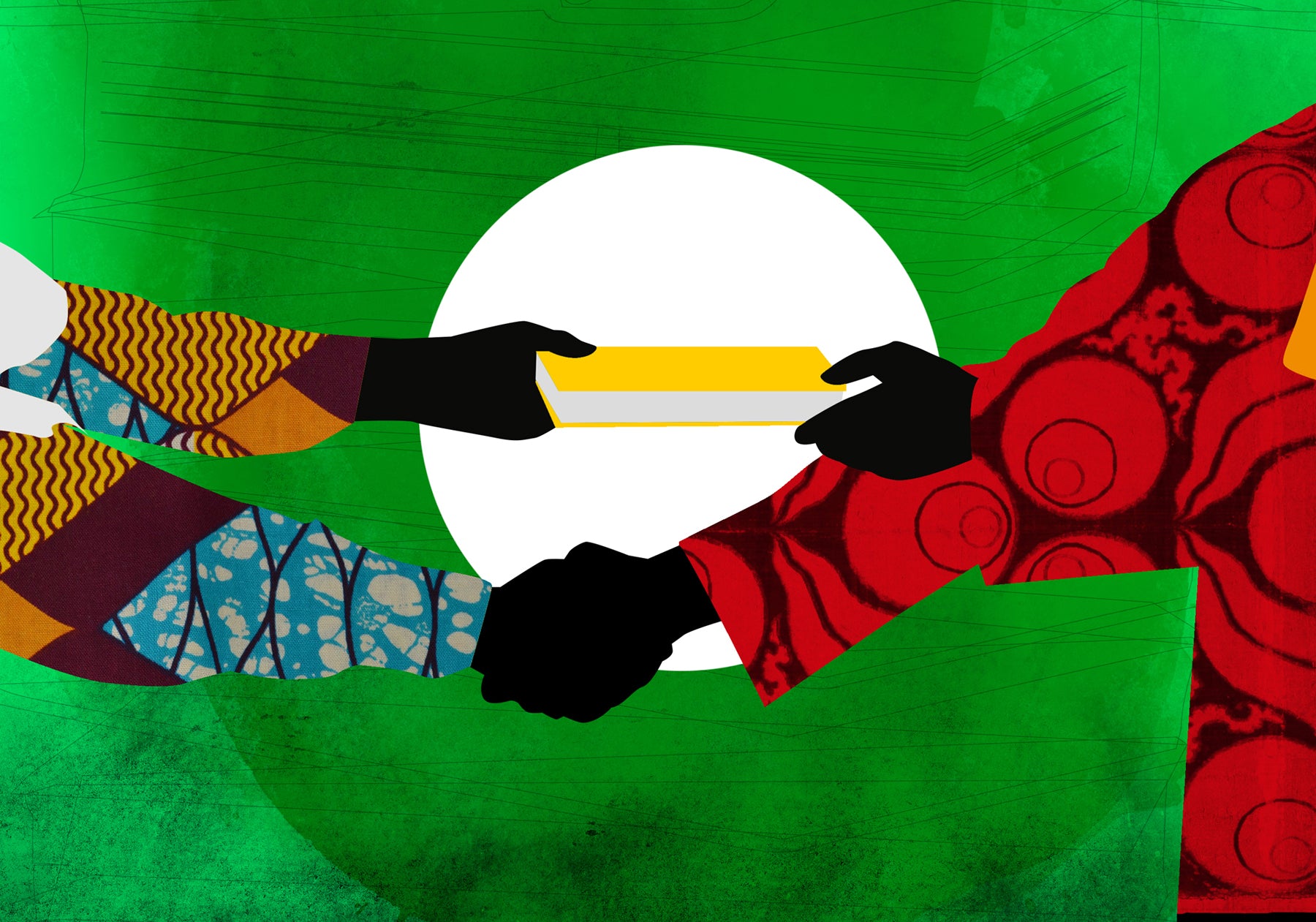

Feature image by Alvaro Tapia Hidalgo